Plot development in videogames

Here is the extent of my thoughts on getting a story told and a videogame played at the same time, after nine years of iterative development on Scout’s Journey.

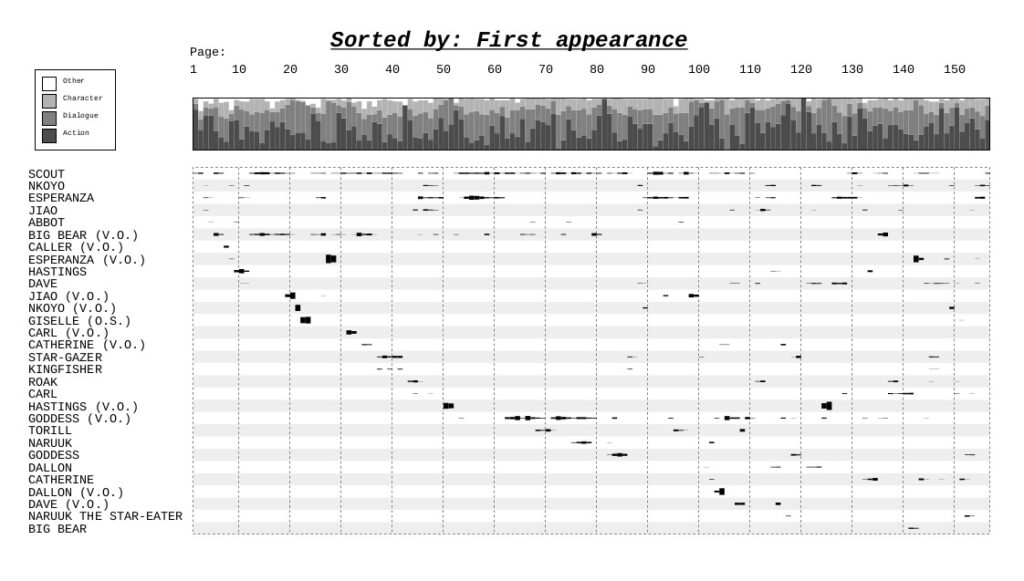

Most players’ attention span will peak near the beginning of a game. After a certain time, players may lose interest or go off to farm items or repeat a boss fight indefinitely, thereby halting the plot completely. It’s unknowable. The largest cohesive block of player attention is likely toward the beginning. So if cohesive plot development is going to happen anywhere, it’s in the first half of the game. Probably the first third.

This coincides roughly with the first act of the three-act structure. The three-act structure works for storytelling, but games are non-linear; either the plot can develop several ways according to player choices, or the player can stop or even reload the game. By comparison, the controlled 90-minute setting of cinema is a pristine lab environment.

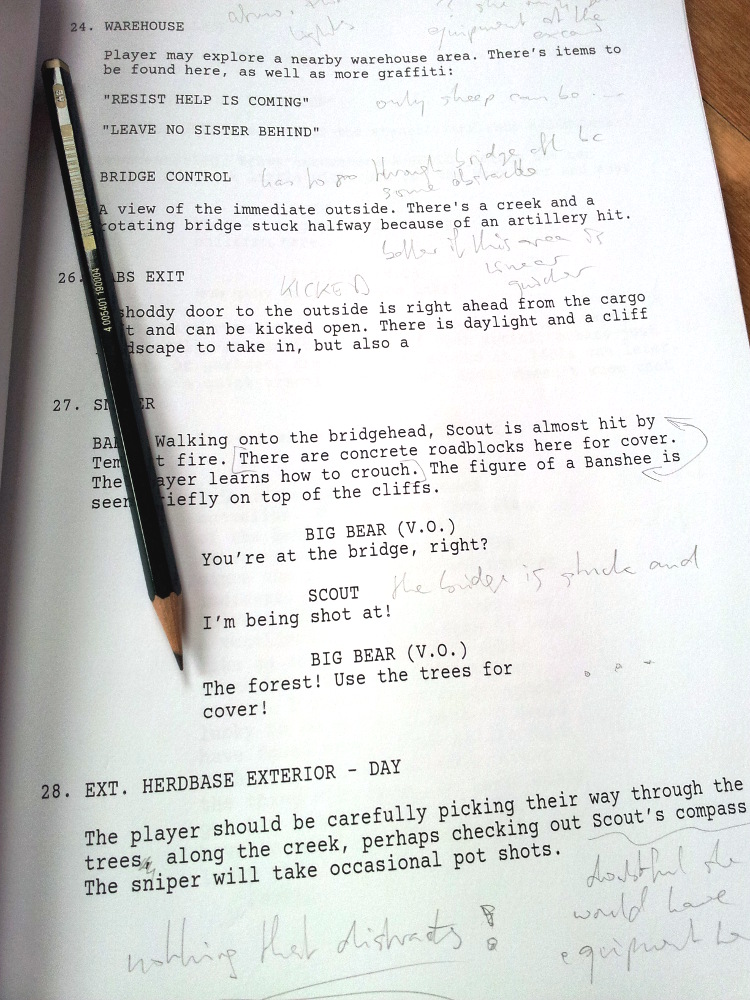

In cinema, we can say that a story has 40 beats or 12 major beats and these beats fall on this or that minute. In games, we’re not so fortunate. We cannot tell after how many minutes the player will pick up the Macguffin or listen to the audio log. It’s possible that they completely miss it. The most we can do is make the main plot really obvious by massive signposting or physically funneling the player into a cutscene to sort of make sure it even happens.

For Scout’s Journey, I’m toying with the idea of large, bright, rotating camera symbols for the player to collect, signposting “here is plot advancement”. (Yes, I do have a better idea than that, but you get the drift.) It’s better than the classic funnel method.

Back to the three-act structure. If it’s assumed that we can best do coherent plot development early on, then the classic structure needs to be skewed to the left. Show more things earlier. Drop more hints. Get the hooks in while you can, before they go off in search of the +5 magic longsword and the ideal ascension kit.

This is actually a blessing in disguise, because gameplay- and content-wise, the early game is usually basic. You don’t want to give the good stuff away too early. The player’s skills and the quality of enemies or obstacles needs to rise somewhat linearly throughout the game. So instead, in those early beats, lay on the storytelling!

If we can skew the ending of Act 1 toward the left far enough, pack that with goodies, and resolve into Act 2 earlier, maybe opening up new skills and content for the player to enjoy, then maybe we can get there before their attention starts to wander. I’d roughly put this at the 30% mark. At that point, we must open the bag of toys.

Because if we skew the plot structure to the left, Act 2 is gonna be a hell of a slog.

If it’s a comedic structure, where the protagonist is on a downtour from their earlier successes and en route to their all-time low, the point where they doubt they can toss the ring into the fire and just want to go home, then there’s going to be a lull in the game right about now, or a feeling of waning rewards for the player story-wise. So what could lift it up again?

Gameplay and content.

Player skills, options, tools and the amount of content accessible to the player are going to be on the rise at this point in a game. They need to be, or it gets very boring. The player has leveled up, so to speak. They’re ready for some challenge. They have better gear. So give them action, and give them exploration. Let them go and do their thing. This is where the plot can stall, it matters little as the key is for the player to enjoy themselves. Here’s the game designer’s playground. Let them go nuts.

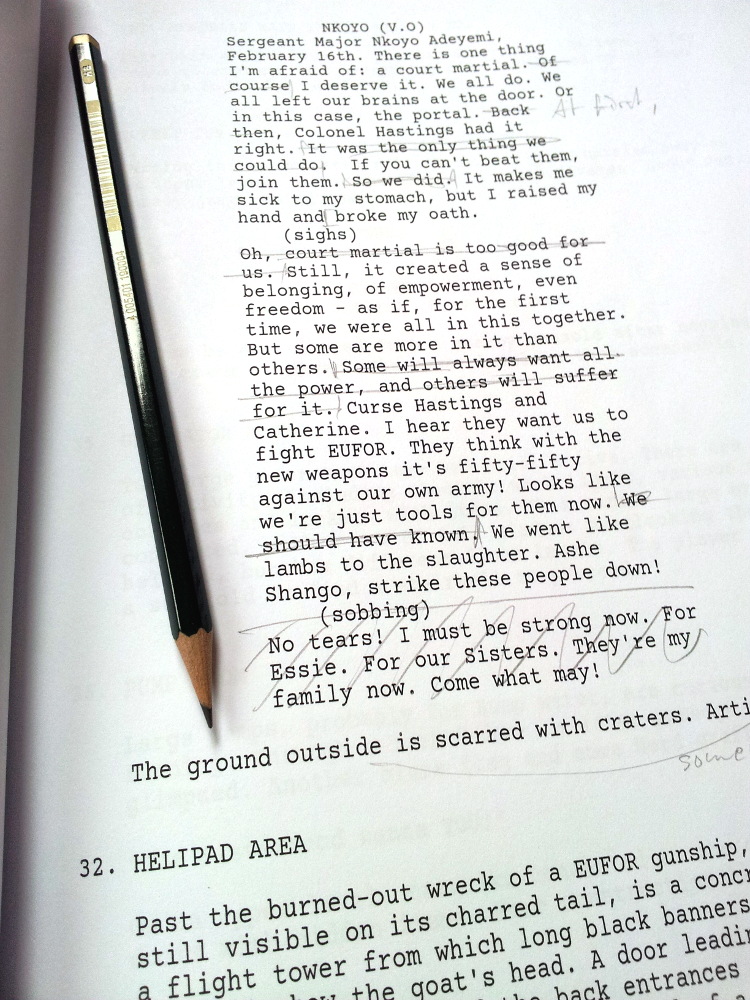

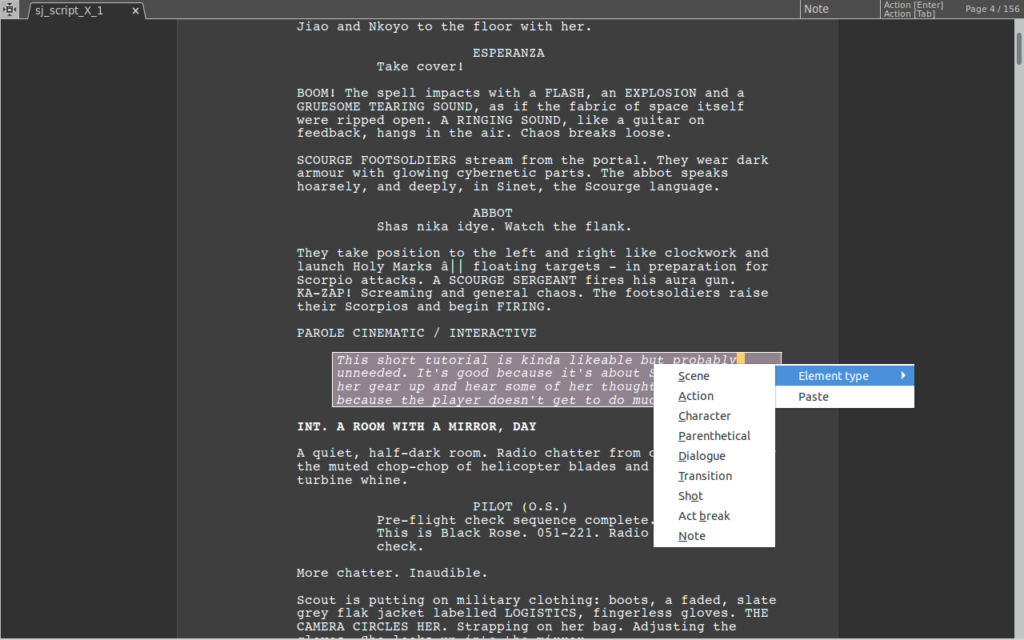

Get Act 2 in among the fray, in bite-sized chunks. The player — if they’re still playing — is busy elsewhere, so this is where we need to bring plot and lore from different angles. This is the place for audio logs, encrypted messages, NPC dialogue, environmental storytelling with cutscenes more sparse and more judiciously paced. Control has firmly been planted in the player’s hands, so let them collect information like loot. Hide the nuts for them to find like a busy squirrel. When the crisis hits, it’ll be even more of a contrast – the player has become a powerful agent, but the character feels crushing hopelessness. This needs to be driven home by the player, too, losing something, or else we get a ludo-narrative disconnect. Here is the place for the +5 sword of ruthlessness being flung away into the lava, or half the controller becoming useless when the older brother dies.

Just make sure it makes sense.

In Act 3, the character picks themselves back up, rediscovers their strength and starts aiming for the Big Bad. The player has a lot of agency left even without the +5 longsword and should relish the upswing. This is when you throw the hardest stuff at them, and when the risk of ludo-narrative dissonance is smallest. Up and up! The character becomes the hero with and through the player’s support. All is pulling in the same direction, to the resolution.

If this all sounds like “railroad them into Act 2 while they’re willing, shower them with toys in Act 2, top it off with a joyride”, then yeah, that’s not far off. Just make it a good ride.

The early railroading, getting in as much of the plot as you can, is less of a problem because the player doesn’t have full agency anyway. You’re not instantly giving them the endgame skills and monsters. They’re getting their feet wet with the game, growing into it. They may even welcome the plot development if it helps them in that.

Please note that railroading here doesn’t mean “non-interactive”. It just means the first 30% of the game look more like they’re “on rails” compared to the middle, which is the “candy store” part. There’s no branching plot and no open world before that point. It’s just a careful string of breadcrumbs. Then the big thing happens, we’re in Act 2, and bam!, the world is your oyster.

Two main dangers: Act 1 is so boring that they stop playing. This can be countered by bringing Act 1 storytelling in line with the player discovering the world and its mechanics, supporting rather than hindering. To a large degree, it will help if the player can strongly identify with the protagonist and begins to root for them. Or the protagonist’s crisis at the end of Act 2 feels so disconnected from the player’s state of power that they can’t get over it. This may be prevented by solid storytelling and making the crisis a consequent outcome of the player’s own actions (the try/fail-cycle).

Of course some players really just want to let off steam, or relax for a while. These players will see story as an obstacle. They will balk at the idea of cinematic cutscenes. We’ve all heard it: “Don’t take control away from the player”. That’s fine, it’s just the point where it needs to be said that there are other games for that. That is not our audience. You just can’t please these players with a story based game. There’s no use in trying.

For story-based games, though, and for everyone who looks forward to the cutscenes in classic games and feels for the protagonist, this is the best stab I can give it and it’s the method used in Scout’s Journey.